Easter looms on the holiday horizon! And as it falls on April Fool’s Day this year, my thoughts naturally turned to history’s greatest meeting point of religion and humor: Monty Python’s Life of Brian. But as I looked at the movie, and the controversy around it, I came to a startling realization.

Life of Brian can teach us how to live.

Unfortunately, a lot of the controversy around the film’s original release overshadowed its message. Because, unlike most Python movies, or most great comedies, it does have a message.

First, a caveat. I’m not in any way here to disparage the actual Gospels, Psalms, Shewings of Julian of Norwich, Ramayana, Hadith, or Deuteronomy, simply to point out a couple of valuable morals hidden within one of the greatest comedies of all time.

A Brief Historical Interlude

I assume, if you’re on this site, that you know plenty about Monty Python, but I will give you an incredibly quick recap in case you need it. Life of Brian was the Python’s third film. Their second film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, was a huge hit. (Like, an enormous hit, and an incredibly important cultural moment, which always feels weird to me since I grew up later with Monty Python as a cult thing that nerds quoted instead of having actual conversations with each other.) The Pythons went on a world tour to promote Holy Grail, and at some point during a layover at an airport someone asked what their next project should be. Eric Idle said: “Jesus Christ: Lust for Glory”—either to the other Pythons or to the press, and after they stopped laughing they thought about it and decided to go ahead with it.

Life of Brian follows Brian, an unassuming young man growing up in 1st Century Judea, who tries to join an anti-Roman movement before accidentally becoming a messianic figure. After months of research they created what may be the single most accurate film about the 1st Century C.E. It leaves both The Last Temptation of Christ and The Passion of the Christ in the dust (which it promptly shakes it from its feet as it leaves town)—from the tense relationship with the Romans to the proliferation of philosophers and self-proclaimed messiahs to the fractured ideas of how to oppose occupation. The Pythons decided that Jesus himself was not really a good target for satire (they all liked his teachings too much) but the structures of religion were fair game, as were the various political factions that had sprung up and could mirror the ever-more-ridiculous splinter groups of the 1960s.

A Note On Jesus

Life of Brian is really explicitly not about Jesus. That gentleman does have two cameos, and the film is completely, almost weirdly reverent during each of them. I say weirdly because “reverence” isn’t a word that comes up much when discussing the Pythons. First, it’s made quite clear that the stable down the street from Brian’s—you know, the one with Jesus in it—is bathed in holy light, surrounded by angels and adoring shepherds, the whole shmear. The second cameo comes when Brian attends The Sermon on the Mount. Not only is the Sermon well-attended, but everyone approves of the few snatches of the speech they’re able to hear. He’s also referred to as a “bloody do-gooder” by a former leper who lost his revenue stream when Jesus healed him. If you somehow only learned about Jesus from Brian, you’d have an image of an objectively divine person who was a hugely popular public speaker, and who could actually heal people. This is a more orthodox version of Jesus than the one presented in Last Temptation.

Predictably, however, the film caused a firestorm of controversy when it came out.

The Pythons vs. the World

EMI, the film’s original producer, pulled out about two days before the Pythons were set to go to Tunisia to begin filming. Eric Idle mentioned this disaster to his friend George Harrison, who mortgaged his house to found Handmade Films, which would later produce such British classics as Mona Lisa, Withnail and I, and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. They decided to premiere it in America first (give yourself few minutes to laugh at the idea of America welcoming a religious satire with open arms) because, well, we have freedom of speech enshrined in the Constitution. What they didn’t expect was that, first, they had to make out wills before they came to New York just in case someone took a shot at them, and second, the people who protested the most vociferously were The New York Association of Rabbis, who were angry at the use of a prayer shawl in the stoning scene (seen above).

It’s worth noting that the film caused its own miracle, because members of different stripes of Judaism, Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and Protestantism all came together to picket film screenings. Despite Life of Brian being banned in some areas of the Bible Belt, the film ultimately benefited from the controversy, opening on 600 screens across the U.S. instead of the original 200, and earning more than expected.

The reason the Pythons were seriously worried comes down to a single person: Mary Whitehouse. She was a teacher who, during the 1950s, became obsessed with the idea that Britain’s moral character was failing, and that the only way to help was to send piles and piles of letters to the BBC to tell them not to allow people to use the word “bloody” on air. She developed two large groups, the “Clean Up TV Campaign,” which became the National Viewers’ And Listeners’ Association, and the Nationwide Festival of Light, which managed to wield some influence with high-level politicians, who in turn pressured the executives at the BBC to listen to her demands. Amongst these demands were: less war footage shown on TV, lest the British public become too pacifistic, less sex in general (surprise), and… less violence on Doctor Who?

Wait, Doctor Who?

Huh. Yes, she was angry about the “strangulation—by hand, by claw, by obscene vegetable matter” in “The Seeds of Doom.”

Noted.

Whitehouse’s highest profile success came just two years before Brian’s premiere, when she sued the publishers of Gay News (exactly what it sounds like) over a poem called “The Love That Dares To Speak its Name.” The poem, a play on the phrase ‘the love that dare not speak its name’ from Oscar Wilde’s boyfriend’s poem “Two Loves,” upped the homoerotic stakes by centering on a Centurion who has pretty unholy feelings for Jesus. Whitehouse later told a reporter that “I simply had to protect Our Lord.” The specific thing they sued for was “blasphemous libel” (also exactly what it sounds like) and, in a trial where the prosecuting attorney told the court: “It may be said that this is a love poem—it is not, it is a poem about buggery,” and which only allowed two character witnesses for the defense rather than any experts on pornography or theology, the jury found for Whitehouse (10-2!) and Gay News was fined £1,000, while publisher Denis Lemon was fined £500 and received a nine-month suspended prison sentence. This was for a crime that had not been prosecuted since 1922.

So when someone in Brian’s crew leaked 16 pages of the script to the Festival of Light, the Pythons became considerably more nervous about their movie.

At first the group only encouraged Christians to pray for the failure of the film, but that soon turned into the usual letter writing campaigns and pressure on local councils. The Pythons decided to get out ahead of any backlash by agreeing to a televised debate with two prominent Christians on the chat show Friday Night, Saturday Morning.

The debate (embedded below) manages to be more painful than you might reasonably expect, and I urge everyone to watch it. Historically speaking, it’s an extraordinary document of a cultural moment that could have only happened in the 1970s. A pair of young-ish satirists speak earnestly about their intentions for the movie, telling the interviewer that, after devoting themselves to studying the Gospels, they all came to the conclusion that they couldn’t make fun of Jesus. It’s heartbreakingly sweet, given what comes next: Mervyn Stockwood, then Bishop of Southwark, clad in purple robes and fondling the largest crucifix I’ve ever seen anyone wear (and my great-aunt was an old-school nun) and Malcolm Muggeridge, a former editor of Punch who converted to Christianity in his late 60s—after a life of public debauchery (and who, along with Mary Whitehouse and a pair of British missionaries, was a cofounder of the Festival of Light)—proceed to badger and heckle the two Pythons, talking over them, insulting them, and refusing to engage in any true debate beyond wagging their fingers, while their moderator, Jesus Christ Superstar lyricist Tim Rice, sits back and watches rather than adding any points from his own experience working on a theologically thorny project.

The two older men vacillate wildly between mugging for the audience and talking over Cleese and Palin in horrifyingly condescending tones. It isn’t a debate, because the Bishop and Muggeridge aren’t listening, they’re simply pontificating on the state of the world and treating their opponents like naughty schoolboys who need to have their knuckles rapped (I’ll remind you that Cleese and Palin were pushing 40 at this point).¹ The Pythons did manage to get some excellent points in, with Cleese saying, “Four hundred years ago, we would have been burnt for this film. Now, I’m suggesting that we’ve made an advance”—but it became clear that the two Christian leaders were not there for either the five-minute argument, nor the full half-hour—they were just there to berate the Pythons.

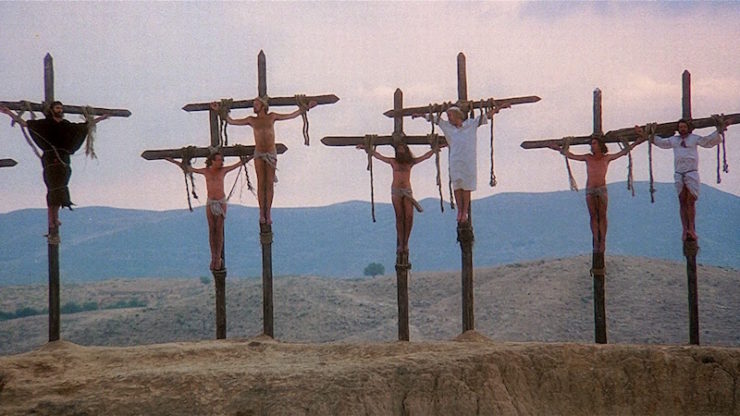

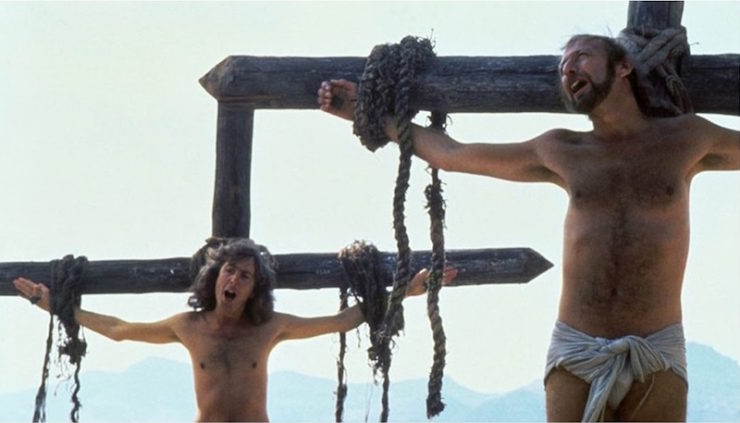

The men’s biggest concern was with the ending–the musical chorus line that happens during Brian’s crucifixion. (Can I admit something? Just typing that line made me grin uncontrollably. Perhaps I’m not the best person to write about this, maybe my position is already too clear.) When I re-watched the debate and documentary for this post, I was reminded that both of them are really hung up on the crucifixion. They keep returning to that moment above all others in the film, with Muggeridge in particular expressing outrage that anyone could make a joke out of moment that has inspired the greatest works of Western art in the last 2,000 years. Stockwood further asks, “Why lampoon death? That sort of worried me. I don’t think one would make a farce about Auschwitz or of death … it was a shattering thing what happened to [Jesus]–crucifixion.”

Which, hm. First, what the Pythons are doing in their crucifixion scene is stripping the uniqueness from Brian.

He’s the one we’ve followed through the story, so even if he isn’t the Messiah, we’re still on his side, empathizing with him, rooting for him, so that when he’s captured and sentenced to crucifixion it’s legitimately terrible, but the way the Pythons deal with it is to show us a long line of condemned people all being processed with ruthless efficiency by Romans. It shows crucifixion as it most likely actually was: just another day in the Roman machine, exacting obedience through public torture. I have to wonder if that’s part of what the two men are objecting to. Because generally in the West, when you think of crucifixion there’s really only one Guy who comes to mind. Even when Kubrick made Spartacus, about a Roman pagan who was crucified about 40 years before Jesus’ most likely birthdate, he plays with imagery that was used in Christian art to evoke a sense of holy martyrdom around his character. (The “I am Spartacus” line is also played with in Life of Brian.) It became so iconic a part of Jesus’ story that according to Catholic lore, Peter specifically asked to be crucified upside down so as to not exactly replicate his Master’s execution.

So for Life of Brian to take that moment and turn it into a song-and-dance number isn’t just the usual Python silliness, but something much deeper… but I’ll come back to it in a minute.

The debate finally came to an end with the Bishop and Muggeridge shouting down all of the Pythons’ points. Tim Rice thanked the men for their time, but the Bishop managed to get the last word by snapping, “You’ll get your thirty pieces of silver, I’m quite sure,” while Rice murmured, “I hope that the film won’t shake anybody’s faith.” Then, in what is possibly the most whiplash-inducing moment of the decade, Rice cut to Paul Jones performing “Boom Boom (Out Go the Lights)” in which the singer announces his intent to stalk his ex-girlfriend and beat her into unconsciousness as soon as he finds her. Neither religious leader—still onstage for the performance—saw fit to decry this celebration of violence in the media. Not “shattering” enough, presumably.

A Brief History of Jesus on Film

Life of Brian was coming out of a very specific social milieu that has since shifted in ways that would make the film impossible to make now. In order to get that, allow me to give you an EXTREMELY abbreviated history of The Jesus Movie:

In the beginning was spectacle. The Silent era produced a couple of brief films of the Nativity, and some giant Cecil B. DeMille epics. In the fifties, we got Greatest Story Ever Told and King of Kings, both huge films with casts of thousands that used a syncretic approach to the New Testament. By cherry-picking some of the most famous scenes and quotes from each of the Gospels, and shoving them all into one film, they try to give you an idea of Jesus’ life, and an extremely sanitized retelling of the beginnings of Christianity. In the 1960s we got a stellar Jesus movie, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Gospel According to St. Matthew, which does exactly what it says on the tin – the words and events of Matthew are depicted in black and white via a very tight, constantly moving shot. This film, with its minimalism and aggressively revolutionary Jesus, is often seen as a reaction to the big budget spectacles of Hollywood.

The 1970s created a perfect storm of liberalism, social awareness, musical theater, and the Jesus Freak movement, giving us Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar, both of which were adapted into films in 1973. (Full disclosure: I am inordinately fond of both of these films.) JCS features a long-haired hippie Jesus, Black revolutionary Judas (who’s actually kind of the hero), and Native American Earth-mama Magdalene (who’s a main character rather than a hanger-on.) They sing, at length, about revolutionary movements, selling out, and megalomania. In Godspell we get a colorful troupe of hippies running amok in Manhattan and acting out a stripped-down version of Matthew and Luke like an evangelical Sesame Street gang. (Victor Garber, in a nod to the Christianization of the Jewish historical Jesus, wears a skintight Superman t-shirt throughout the film.) And even Franco Zeffirelli’s far more traditional Jesus of Nazareth (the one that used to get shown on TV at Easter each year) features a complicated, politically-motivated Judas.

In 1979, as people were becoming increasingly disillusioned with most of the revolutionary movements, Life of Brian arrives, able to use the Jesus story as a jumping-off point for their character Brian, and a wide-ranging satire that mocks organized religion, political movements, and Latin teachers with equal glee. Hilariously (?) Martin Scorsese ran into even more controversy, death threats, and low earnings when he made The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)—which, again, is based on a novel by Nikos Kazantzakis and at no point claims to be any kind of canonical gospel—while Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) was released to praise from religious groups and boffo box office, despite drawing on the Book of Revelation, traditional Passion art, and, most notably, The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ, a book describing the visions of 18th century nun Anne Catherine Emmerich, rather than sticking to Gospel-era canon.

But What About the New Testament?

So glad you asked. Talking about what sort of life the gospels want you to lead is fairly difficult. Since there are four of them, and they all have slightly different takes on the teachings that evolved into early Christianity, it can get overwhelming.

Here’s my best attempt:

- Mark = put all of your moral affairs in order, as the end is nigh.

- Matthew = are you poor, but good? Wretched, blighted, suffering, oppressed, but trying your best every day to be decent person? You’re probably going to be okay, kid. Wait, you want me to tell you how? I’m not going to tell you how, that would be cheating.

- Luke = the same as above, but with slightly more flowery language.

- John = put all your moral affairs in order – oh, neat, a miracle! Now keep putting them in order, because the end? Super nigh.

Depending on which gospel you’re reading, you’re supposed to be meek, compassionate, or radically empathetic—like, Betazoid level empathetic. In Matthew, you’re told to be perfect; throughout Mark, you’re told that there were people living then who would see “the kingdom of God come with power,” and in Luke that even the most prodigal of sons would be forgiven.

If you’ll allow me to delicately sidestep the non-canonical stuff because it would take too long, I’ll make my first point: even if you’re trying to align your life with those gospels (or with the more formal teaching of Catholicism, Orthodoxy, or most Protestantisms) Life of Brian actually adds an exciting addendum to those teachings. Because what is the true message of Brian? Be an individual. Be creative, think for yourself, don’t blindly follow people who claim to be in power—for won’t you both fall into the pit?

And above all, don’t be afraid to laugh at authority, especially when its name is Biggus Dickus.

Face the Curtain with a Bow

So, we must come, inevitably, to death. As I said, this seemed to be the sticking point for much of the controversy in the 1970s – far more than any lampooning of the origins of Christianity, it seemed to be the fact that anyone made a joke about crucifixion that was the issue.

Here’s why it’s important. At a certain point in an interview, Palin says that if they focused on the pain and torture of crucifixion it would have ruined the film, because making light of suffering wouldn’t work. But. They do give us the close-up of Graham Chapman’s face, in pain. They give us his hope when the Crack Suicide Squad shows up, and then how crushed and defeated he is when they just stab themselves. They do give us the moment of Mandy and Judith visiting him, and his utter desolation as they leave him. Is it the physical torture of Mel Gibson’s Jesus Chainsaw Massacre? No. Is it a hallucination of happiness that is then cruelly taken away, as in Last Temptation? No. It is a gradual breaking down of every scrap of hope that Brian has. Brian, who is not the Messiah (he’s a very naughty boy), who does not have a seat at Anyone’s right hand awaiting him. Brian, who, weirdly, expresses no religious beliefs of his own at all. Brian isn’t a grand historical figure, he’s just an everyday guy who wants to stand up to an oppressive regime. He could be anybody, he could be us, and we watch his life and hope be stripped away from him. And then Eric Idle leads him in a song. A death-defying, life-affirming, gleeful Fuck You of a song.

I still remember the first time I watched Holy Grail, but I don’t remember much of the first time I saw Life of Brian. What I remember of it is the ending. I remember watching that chorus line for the first time, and I remember feeling my mouth fall open as everyone began to sing. The idea that you could do that, that you could make something silly and joyful out of a tragedy—that tragedy, the axis mundi of the Western Canon—and just giggle. All bets are off if you can make fun of that. There are no limits to laughter, not even death. For me, this is the moment when Life of Brian joins that lineage of “greatest works of Western art.”

1. Interesting Side Notes: The televised debate between the Pythons and the Festival of Light was mocked to hilarious effect in a Not the Nine-O’Clock News sketch that aired a week later, ultimately asserting that Britain is a nation of Pythonists. You can watch the skit here. In 2014 the BBC revisited the controversy with a surprisingly emotionally-resonant biopic called Holy Flying Circus that highlights the Pythons as decent men men trying to helm a fight for free speech without losing their senses of humor. I recommend it to all the Pythonists reading this.

Leah Schnelbach asks herself at least once a day: “WWBD?” Come call her a blasphemer on Twitter!

IIRC, there is a third at the end, when Jesus offers to carry the cross of a man being marched to crucifixion, who runs off and leaves him to be killed in his place. Rather makes Jesus Christ, Lord and Savior of all mankind, look like a fool.

@1 I haven’t watched Life of Brian recently, but I’m pretty sure it was just some random guy who offered to carry the cross.

As a snarky kid, after I went to the movie, I came out and addressed the protestors. (I was living in Georgia at the time, a place where Christianity is taken very seriously.) I told them that they would prevent more people from watching the movie by saying “Not as Good As Holy Grail” on their signs. As you pointed out, it’s very obvious that Brian isn’t Jesus. But that was the last time I saw the movie. Based on your review, I supposed I’m going to see it again, using the (slightly) less snarky eyes of an (alleged) adult.

@1 and 2: I always thought that the helpful cross-carrier was supposed to be (the Python version of) Simon of Cyrene, who had offered to/was coerced into briefly carrying the cross for Jesus in a few of the gospel narratives.

@@@@@ 1, 2, and 4: That was always my assumption as well! Poor Simon. :(

Hmmm … Now it would be interesting to compare and see whether Jesus gets more screen time in Life of Brian or in Ben Hur (whose subtitle is “A Tale of the Christ”).

On the whole, while Ben Hur has a much better chariot race, I think Life of Brian is overall a better film. And almost certainly more historically accurate.

Not being Christian I don’t care but I can see how Christians would be offended.

People have a right to take offense and to say so. As long as they don’t descend to death threats or murder attempts.

@2 I could easily have mis-remembered it (hence the “IIRC”), so I’m prepared to be proven wrong about that.

Life of Brian is undoubtedly the best movie the Pythons made, in terms of story, character, and dialogue. Holy Grail is funnier, and more quotable, but it’s a bunch of skits with a theme and just barely holding together a plot. The rest of the Python films are just a bunch of skits, with no overarching plot (Meaning of Life) or no attempt at a theme (And Now for Something Completely Different and Live at the Hollywood Bowl).

Yes, there are skit-like pieces in LoB: The hermit, the haggling, the Latin lesson. But they move the plot along, rather than being the meat of the matter like in MTatHG.

I’m surprised you didn’t mention my favorite scene: falling off the tower into an alien UFO, ending with “You jammy bastard!” Completely nonsensical, and delightful.

Brian: Look, you’ve got it all wrong! You don’t NEED to follow ME, You don’t NEED to follow ANYBODY! You’ve got to think for your selves! You’re ALL individuals!

The Crowd: Yes! We’re all individuals!

Brian: You’re all different!

The Crowd: Yes, we ARE all different!

Man in crowd: I’m not…

The Crowd: Sch!

That song, “Always Look at the Bright Side of Life,” stuck with me for years, and I would hum it to cheer myself up when things got difficult.

And y’know, the song at the end kinda sums up the whole concept of the movie, the point that those protesters missed: don’t take life so seriously, you’ll never make it out alive.

It was in no sense a protest or a political or religious comment, but I inadvertently released some twenty live adult house crickets in the snack bar of the cinema where I went to see The Life of Brian.

On looking back, it seems a suitably Erisian thing to have done, but it was unintentional. My lizards had to tighten their belts until I could get back to the pet shop that week.

“Because, unlike most Python movies, or most great comedies, it does have a message.”

I don’t think I agree with this statement. Good humor has to be based in reality and in truth, other wise I see it as just silly and pointless and I have never liked silly humor.

Benny Hill being a good example of just plain silly. Don’t get me wrong Python always had ‘silliness’ in it’s humor but always seemed to have an underlying subtle or not so subtle intent to most of its humor. Not only did they help me to laugh at serious things but at myself.

It seems pretty clear the point was to mock Christianity or at least organized religion with a side wink at ‘Revolutionaries’.

Reg:All right, Stan. Don’t labour the point. And what have they ever given us in return?

Xerxes:The aqueduct.

Reg:Oh yeah, yeah they gave us that. Yeah. That’s true.

Masked Activist:And the sanitation!Stan:Oh yes… sanitation, Reg, you remember what the city used to be like.

Reg:All right, I’ll grant you that the aqueduct and the sanitation are two things that the Romans have done…

Matthias:And the roads…

Reg:(sharply) Well yes obviously the roads… the roads go without saying. But apart from the aqueduct, the sanitation and the roads…Another Masked Activist:Irrigation…

Other Masked Voices:Medicine… Education… Health…

Reg:Yes… all right, fair enough…

Activist Near Front:And the wine…

Omnes:Oh yes! True!Francis:Yeah. That’s something we’d really miss if the Romans left,

Masked Activist at Back:Public baths!

Stan:And it’s safe to walk in the streets at night now.

Francis:Yes, they certainly know how to keep order… (general nodding)… let’s face it, they’re the only ones who could in a place like this.

Reg:All right… all right… but apart from better sanitation and medicine and education and irrigation and public health and roads and a freshwater system and baths and public order… what have the Romans done for us?

@10

Drop the mic dude!

That is a succinct, but exhaustive commentary on thos moment in history.

I’m kind of a young’un for this, but I was just the right age to counter the protests against Dogma, another wonderful film with religious messages and my other go-to Easter movie along with JCSuperstar. I always wondered why there was so much ire against those films, but no real protests against the Passion, which was basically Jesus Gets His Ass Kicked for 2.5 hours.

@15: Brought peace?

As another sidenote/tangent, Mary Whitehouse was also paid due homage in Pink Floyd’s “Pigs (Three Different Ones)” on their 1977 album Animals as a “house-proud town mouse,” “all tight lips and cold feet,” “trying to keep our feelings off the street.”

Reading the article and recalling that the Floyd were among the angels who saved Holy Grail by investing in the film when Python ran out of money during production, I do wonder about the timing of the Brian script leak and whether that contributed to Roger Waters’ hostility (not that he’d need an excuse to go off on a smug right-winger like Whitehouse). Going by the Wikipedia entry for Life of Brian, it doesn’t sound like Python had a script when Animals came out, though the Pythons’ early pre-production work on the film was roughly contemporaneous with the Floyd’s work on the record.

Hrm.

Anyway, thought that might be of interest to someone. And thanks for the great article.

The Jesus Freak movement. Oh man, one of those weird 70’s things that got huge and then just disappeared. Possibly dissolving in a cocaine binge at Studio 54 after Saturday Night Fever.

Leah mentions it in the side notes, but I’ll mention it again in case anyone missed it, there’s a great comedy drama about the release of Brian called Holy Flying Circus, which manages to cover all the facts, whilst still looking like something the Pythons would have made, right down to having the part of Michael Palin’s wife played by the same actor who plays Terry Jones. It crops up every so often on the BBC, and I’m sure I couldn’t condone looking elsewhere for a copy, ahem.

And I can never hear “Always look on the the bright side of life” without thinking of the rendition at Graham Chapman’s funeral by all the Pythons and his family, which is incredibly touching (if slightly sweary):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fsHk9WC7fnQ

*edit, Oh yes, one last thing, I used to have a Latin teacher who was identical to Clease’s performance, right down to grabbing you by the ear and forcing you to decline verbs in front of the whole class. He’d been at the school long enough to have taught my friend’s dad, and we all kind of accepted that for learning a dead language we might as well have a teacher who behaved like it was still the 1950’s.

“Both of them are really hung up on the crucifixion,”

*groan*

@22 Nailed it.

Don’t be cross with me.

Amongst these demands were: less war footage shown on TV, lest the British public become too pacifistic, less sex in general (surprise), and… less violence on Doctor Who?

I’d heard about Mary Whitehouse – there was even a TV comedy sketch show in the 1990s called “The Mary Whitehouse Experience” – but I’d never heard about their first demand. Very interesting. Bart Simpson would disagree: “Lisa! If you don’t watch the violence, you’ll never get desensitised!” So real violence was thought to make people less violent, but fictional violence would have the opposite effect?

Life of Brian is really explicitly not about Jesus. That gentleman does have two cameos, and the film is completely, almost weirdly reverent during each of them.

Yes. And note that this is completely different from the treatment of God in “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” in which he is portrayed as an irascible and pompous Terry Gilliam animation; without, as far as I know, attracting any criticism whatsoever.

@18, ‘they make a desert and call it peace.’

There were definitely worse things than being conquered by the Romans, one benefit the Pythons didn’t mention was citizenship. Not everybody was a Roman citizen but it wasn’t that hard to become one and there were all kinds of perks attached.

The problem in Judea, aside from Jews being ornery creatures, was the Romans found our religion weird and uncivilized and kept offending both inadvertantly and on purpose.

@15

Nicely done copying the script of a very funny scene but what about the point you were trying to make re: mocking Christianity/religion? As noted in the story they didn’t go after Jesus, he’s in the movie a few times and generally respected. What’s being mocked is humanity’s propensity to follow anyone and worship anything without critical thought and to commit heinous crimes in the name of what or whomever they follow even if the object of worship tells them not to. Just look at the poor old guy in the pit!

Just cut and pasted. I can see how Christians could take offense but I don’t myself. I really enjoyed the deconstruction of liberation movements. And how they tend to be more about other people wanting to be in charge than righting wrongs.

@18: Peace…SHUT UP!

I think you missed one, maybe two Jesus films (I don’t count The Robe).

1. Brian Deacon in ‘The Jesus Film’ [sic!] (based on Luke’s account)

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0feZQkHbCkM ]

2. The Jesus part of ‘The Bible’ miniseries

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bible_(miniseries)

I was in a stage production of Godspell and it was amazing!

Which is, of course, a particular insult to the clergy, whose job it is to lead people in worship. After all, if this is what people are like, then they are engaged, not in an act of good, but in fleecing the gullible.

And, while the portrayal of Jesus is quite orthodox, it is given in a context that is intended to make people question the rightness of orthodoxy, which, again, is a threat to the establishments that define and promote orthodoxy.

@17, First I would point out that there were some protests about “The Passion”, especially by some Jewish folks who thought the film might lead to a new wave of anti-semitism. Second, I would say, that the biggest problem with Dogma is that despite Kevin Smith’s claims to being Catholic, it doesn’t really demonstrate that he understands anything about Catholicism. They completely get indulgences wrong (And they are not that hard to get anyway), the whole God in a coma thing is just plain weird. There are plenty of ways to satarize the Church or critique it, but this plays much more like Jack Chick’s vision of the Catholic Church, than anything else.

Saw it in the Isle of Man on a family holiday in 1980 – it was banned in Ireland! (Not that that was something that we took terribly seriously – banned books and certain other things were easy enough to get, and Life Of Brian would have circulated freely except that it came out just before video recorders were ubiquitous.)

@31

See, now how come when I say that, I get moderated? :)

I saw it first in Melbourne, where I live, along with a short Python send up of travel documentaries “…And back to Venice and more of those f…ing gondolas!” which my brother and I still joke about, using “gondola” as an adjective. Then I saw it again in Israel, where the audience roared with laughter, with some almost literal rolling in the aisles. No protesters. Actually, none in Melbourne either, at least not when I went.

You know, people still quote,”What have the Romans ever done for us?”

A friend of mine, a very religious Christian, complained about it till I suggested she actually go to see the thing, which she did. She loved it! If someone like her got it, why did so many not? I wonder how many protesters never actually bothered to see it?

A bit like all those people who demand the banning of Harry Potter without having read the books.

Along the same lines, I highly recommend reading God Is Disappointed in You [Mark Russell, Shannon Wheeler], a retelling of the Bible. Raised a Roman Catholic, I studied Catechism, not the Bible. I wanted to catch up on what I missed, sort of.

As an Orthodox Christian, a fan of history, and a fan of good humor, I can say I always thought this movie was funny and actually, respectful of Christ. I was more applaud and offended by the Passion of Christ than this film. I mean, it is evident, that the creators were using the motif of Christ’s life and times to write a story about a common man turned revolutionary turned false messiah (plus it is a great insight in how we are so desperate for gurus). Plus, the film is just so historically accurate. I appreciate the humor of the chorus-show song at the crucifixion scene because yeah, life can be pretty grim so we could use a bit of a “bright” perspective on life. We often say that the Orthodox church emphasizes a bright sadness, or joyful sadness. Isn’t this what life is? Both joy and sadness. I think the crucifixion scene in Life of Brian for a devoted Christian, can be a revelation…that wait! We are called to be indeed sober minded and yes, death is terrible but life is something to celebrated even if it is a times to quote “a piece of s**t when you look at it.”

side comment about “all of their films” – why do so few people remember Jabberwocky?

@38

Jabberwocky is not a Python film. It was directed by Terry Gilliam and starred Michael Palin but no other Python was involved.

@39 It is the same with Erik the Viking, I know so many people who think it is a Python movie because it has Terry Jones as director and has Jones and Cleese in it.

Saw this at my small local cinema. Can still recall it. I have never laughed so much in my life. Tears streaming from my eyes. Ribs hurting. So many jokes. This is right up there with the best film comedies ever: Airplane & Groundhog Day.